The DWW Postgraduate Fellowship Programme (PGF) was set up to improve and strengthen the quality and delivery of healthcare provided to Rohingya refugees and local host populations at health facilities primarily located in camps around Cox’s Bazar.

“When I woke up this morning, the lake outside my window had extended; I can no longer see its borders on either side. Three days ago, the view was of fields where a woman in red salwar kameez and billowing scarves walked, cows grazed, and a man harvested a section of knee-high foliage. This morning, through the rain, I can just about make out two figures picking their way across what I can only imagine is a very muddy path lining the distant border between this lake and the next. Later, a tractor comes and ploughs the field that is hidden beneath the water. Rainy season is here, and temperatures have dropped from around 38 degrees C to a mild 28.

My arrival in Bangladesh the weekend after Eid gave me a warped perspective of the country.

Dhaka was

Bicycles gliding past each other,

Smiling faces. Curiosity.

Stalls, mostly closed,

Dogs that couldn’t be bothered to bark.

A man shouted a welcoming ‘good, good’ at me, as I walked along the street.

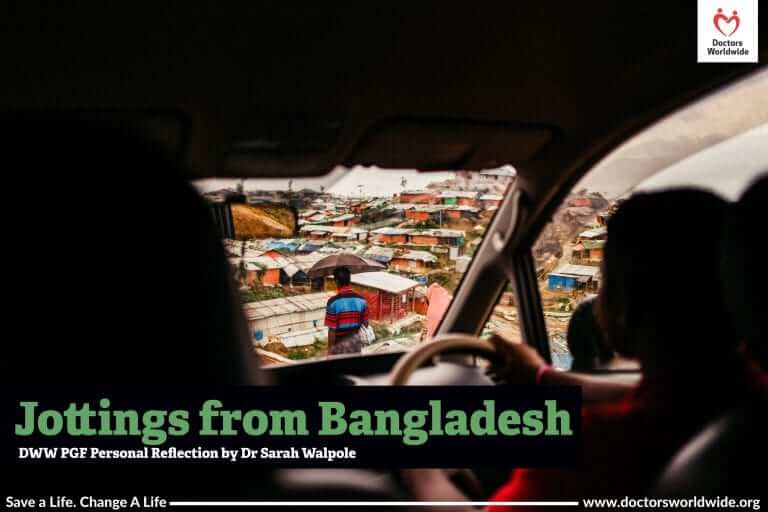

The contrast when I arrived in Cox’s was palpable, from jostling for bags as they were pulled off the trolley at the tiny airport, to traipsing and slip-sliding along the muddy road-sides hoping not to fall into the open sewer on one side or the fast moving tuks on the other, to arriving in an apartment block reception that I mistook for a mall, it being so large and buzzing with the chatter of people stood and sat all around.

According to census data, the entire Cox’s Bazaar district was home to 2 million people in 2011. It’s always been a destination for Bangladeshi tourists, but now it’s home to an extra 1 million Rohingya and an unknown number of humanitarian workers. I’ve been to one ‘health cluster’ meeting since I arrived (group chaired by World Health Organisation to coordinate the health response and feedback to overall coordination of humanitarian response). An attempt to identify and coordinate those providing psychosocial interventions found that there were 77 organisations working on this area alone. It seems that most humanitarian workers/NGO staff here are on one-year contracts, with trips out on leave every 6 to 8 weeks.

You can see the strain that this crisis has put on local infrastructure. Like most people working in the camps, we are based in Cox’s Bazar town, which is a 2-3 -hour drive away. The shortest route to the camps is closed to vehicles as the road is being resurfaced, and the alternative route is more pothole than road. The traffic is heavy and sounds of bustling markets and liberally applied horns abound. The driver told me with amazement how he had seen on television that in America and the UK, cars drive in one line and hardly ever use their horns.

(Trigger warning: some of the following content contains distressing experiences).

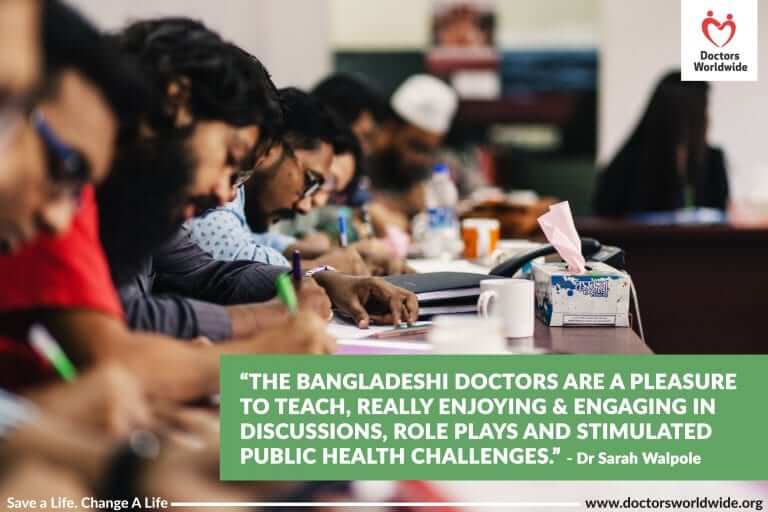

The Bangladeshi doctors are a pleasure to teach, really enjoying and engaging in discussions, role plays and simulated public health challenges. Each week I feel I’m getting a little closer to having the teaching tailored to their level and their interest. Three days a week I visit a camp clinic and supervise one of the doctors, discussing their patients and their management. These are such varied experiences. At the clinic in an ‘Age Friendly Space’, the doctor listened calmly; half of the patients talked about violence that they’d suffered in Myanmar and the ongoing physical and mental health problems. A lady was tearful as she described being beaten up for trying to protect her son as he was taken away by the Myanmar army. A man had severe deformity and back pain after being beaten with a gun barrel. Rohingya volunteers at the clinic were smiling and friendly as they supported their older community members physically or by translating. In one health post I visited, the doctor, who had been drafted from another facility to cover sickness, was faced by the unfamiliar clinic and a large group of waiting patients.

The first challenge was finding the right clinic. Our driver accidentally dropped me at the wrong one, so as I introduced myself to the doctor and paramedic, they returned questioning looks, wondering what I was doing. I managed to communicate who I was looking for, and the paramedic kindly took me on the 15-minute walk to the next camp shielding us from the rain with a large umbrella. We walked along a road full of pedestrians; many men wearing lungis (wrap around cloth, like sarong) carrying one or two 30kg sacks of rice or a gas canister on their shoulders, women mostly wearing a niqab (covering their face apart from their eyes) and children running around variously naked or with some clothing on. After descending a slippery muddy bank, I didn’t quite make the width jumping a stream in full flow and splashed myself and some onlookers. Finally, we dodged under tarpaulins and between stalls along what in another setting might have been called a high street. The clinic patients included a younger man with a bacterial skin infection, an older man severe wasting and an exacerbation of chronic heart and lung problems, a woman with a fungal skin infection, a man with likely COPD (from smoking) and lots of children with colds, chest infections and/or diarrhoea.

In the next couple of months, the rainy season will only increase the risks of food poisoning and infections for those living in bamboo and plastic sheeting homes. Beyond that, there is no endpoint or end place in sight. Bangladeshis talk about the Rohingya returning to Myanmar, and a new road has even been built along 2kms from the camps to the Myanmar border, but it doesn’t seem that will be a viable option any time soon.

PGF Impact Review, 2018 – 2019:

- Trained 99 medical doctors over 4 cohorts representing nearly half of all the medical doctors in the Rohingya camps.

- Benefited over 900,000 patient consultations with doctors trained through the PGF

- 201 sessions (787 hours) of clinical shadowing conducted by DWW medical faculty

- 602 additional professional certificates achieved including MISP for Reproductive Health, ETAT, BLS, and LSHTM Health in Humanitarian Crises (online)

- 36 NGOs, iNGOs and GOs represented across trained cohorts

- 138 sessions (423 hours) of teaching conducted by DWW medical faculty

- Over a 20% increase from baseline knowledge demonstrated by each participant, on average, in addition to new skills learned.

- Over 1,500 workplace-based assessments recorded in personal logbooks including case-based discussions, directly observed procedural skills, mini-clinical evaluation exercises, and reflective practice by DWW medical faculty

Since the completion of the PGF programme, Doctors Worldwide have introduced a new project in Bangladesh in partnership with IOM (International Organisation of Migration). Launched in April 2020, the project – DICE (Doctors Worldwide Improving Care in Health Emergencies) – aims to introduce and build emergency care in refugee camps and communities in Bangladesh. Support the DICE Programme here.